The Struggle for Social and Economic Justice in South America

These are difficult times for those who hope for substantial progressive change. The implosion of Western capitalism, despite the vast economic devastation it has wreaked, has not lead to significant popular questioning of its fundamental principles nor to a resurgence of a socialist ideals and alternatives. For most North Americans, socialism remains a dirty word, a pejorative to be negatively associated with even most modest attempts at economic reform.

In South America, by contrast, conflicts continue to be seen in terms of an ongoing struggle between global capitalism and socialist change. While some of these pronouncements, on both sides, may be reasonably argued to be more rhetorical than literal, demands for significant social and economic change continue to reverberate in many parts of the continent.

Chile and Bolivia offer intriguing vistas into this process. The two countries share interesting similarities despite evident differences. In Bolivia, Evo Morales’ Movement toward Socialism has brought an indigenous majority to the presidency and congressional control for the first time in Bolivia’s history. A new constitution recognizes the many indigenous groups that Bolivia comprises as nations within the nation; a strong (if possibly unenforceable) anti-discrimination/anti-racism law has been enacted; and Bolivia’s deeply impoverished people have gained some important economic benefits. In Chile, forty years since the country’s bold attempt to implement socialism through democratic means was brutally aborted by Pinochet’s military dictatorship and after twenty years of centrist coalition government, a “business-friendly” right-wing is now firmly in control. Yet, in both countries, there are signs that the ideological struggle continues. Evo’s victory does not assure socialism, far from it, nor does Piñera’s ascension to the presidency of Chile mean its final demise. In both countries, groups and individuals continue their ardent struggles to achieve significant societal change.

Remembering Chile’s past in order to look forward to its future

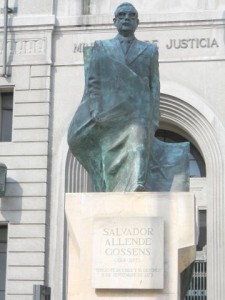

From 1970 to the violent overthrow of the Unidad Popular on September 11, 1973, Chile was attempting to do something unique: to transition to socialism through democratic means. The intensity of the reaction against this process — the ruthlessness of the seventeen-year dictatorship — testify to the importance not only of stopping Allende, but of erasing from the collective memory the possibility of a people revolutionizing their own society. Rule by terror demands more than acquiescence. It demands that people repress their hopes and aspirations, deny their perceptions and their understanding. Chile’s loss extended far beyond its borders, sending a message to people everywhere that the price of struggle is too high to bear.

Despite the overwhelming media insistence to “move on” and enjoy the fruits of neoliberalism, Chile reverberates with the insistence on remembering the many who gave their lives to the attempt to change the social and economic order. This past fall, for example, hundreds gathered for a ceremony at the Universidad Católica announcing the publication of Premio Nacional historian Gabriel Salazar’s work, Una luz sobre las sombras (“A Light into the Shadows”), that honors some thirty members of the Universidad Católica community who were executed without trial by the military junta, many by being dropped into the sea. The university has never officially acknowledged the assassinations: Another instance where those in authority demonstrate the importance of the past by attempting to deny it.

Speaking eloquently of about the lives and deaths of these courageous Chileans, Salazar made clear that his intent was to look forward. Significantly, Chile’s current student leaders, including the president of the Chilean university students’ association, Joaquín Walker, echoed Salazar’s point that memory is not only to show respect, but also to energize what they see as a continuing struggle.

Even harder than remembering the past is the task of holding those responsible accountable for their actions. The dictator Augusto Pinochet died untried and unrepentant. Unlike South Africa, Chile has never had a court of reconciliation where culpability can be established and acknowledged. A case in point is depicted in the documentary, Imagen Final, (www.imagenfinal.com.ar), that traces the attempt to identify the military assassin of Leonardo Henricksen, the cameraman was shot dead as he filmed the treasonous assault on the presidential palace in the months prior the military coup. The film depicts the ceaseless effort of one journalist, Ernesto Carmona, to find and interview the man who committed this insolite crime in which the victim filmed his own execution. Although Carmona was able to locate the likely assassin, it was impossible to bring him face-to-face with his accusers, to make him accept responsibility for his crime. As one victim of torture told me, Chile is beginning to recognize the victims of the terror, but has dared to confront only a small minority of the perpetrators. How many other such criminals lurk in the shadows of Chile’s past? How possible is it for a nation to move forward while denying its past?

Chilean activists are not naive about the challenge they face. As Jorge Arrate, former government minister, and Allendista candidate in Chile’s most recent presidencial election, said to me, “We are passing through a very dark time.” Fueled by the hallmarks of neoliberalism — a monolithic and pervasive dominant media, large infusions of foreign investment, banks providing credit available far beyond Chileans’ ability to repay — large swaths of the Chilean populace have been effectively depoliticized. But this does stop life-long activists like Arrate. He stressed how he was able to use the televised presidential debates to reach millions of Chileans, more than quadrupling his support in articulating a legitimate socialist vision.

Those whose struggle for significant social and economic change dates back to Allende’s aborted attempt to implement socialism democratically cannot fail to acknowledge the devastation of the loss that has been suffered. The historian and novelist, winner of the Premio Nacional de Literatura, Jose Miguel Vara, who fought the dictatorship from exile, recently documented the violence against Chilean musicians that included everything from the execution of the protest singer-songwriter Victor Jara to the criminalization of playing the quena, the traditional Andean wood flute. Jose Miguel laments the depoliticization of the Chilean people. He has joined with Arrate, Victor Hugo de las Fuente, editor of Le Monde Diplomatique’s Chilean edition, and Manuel Cabieses, editor of independent left publication, Punto Final, to form a group pressing left-leaning candidates and parties to stand up for socialist left that is more than a window-dressed version of the coalition that ruled Chile without significantly changing policies dictated by Pinochet.

Cabieses, now in his late 70’s, stresses the importance of recognizing the degree of ideological defeat that the left has suffered as an essential step towards its reconstruction. Cabieses has kept Punto Final publishing, one way or another from prior to Allende until today, its pages filled with detailed analyses of the Chilean political landscape (www.puntofinal.cl). As I spoke with Cabieses at the end of my time in Chile, we recalled Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, the science fiction epic in which the “firemen” burned all the books they could find and a cadre of people kept great works alive by memorizing them. Keeping the flame lit in Chile, where today’s right-wing government is in the process of damming the pristine rivers of Patagonia to feed the mining industry’s insatiable need for electric power, requires a strong capacity to retain one’s ideals in the face of powerful reactionary forces.